Chinese robots, European lag?

The robotics industry relies on a few key success factors: Massive investment in R&D, technology acquisition, and large-scale deployment of products (even non-achieved ones) to learn through iteration. Starting from a third-world level in this industry in the early 2000s, China followed these precepts.

Europe, on the other hand, faces several obstacles that prevent it from developing the “robotics ecosystem” we would like to see.

The “Great Leap Forward” of Chinese robotics

China never ceases to impress us with its robots. First, there were Deep Seek’s conversational robots. But there are as well domestic and humanoid robots from UBTech and Xiaomi.

We are also seeing large state-owned companies such as China State Shipbuilding Corporation developing autonomous ships, car manufacturer Nio promoting its robotic battery exchange station model, Baidu (with Appolo Moon), Pony and Didi investing in robotaxis, and even Chinese fondue chain Haidilao investing in cooking robots!

But if there is one area where China has surprised us even more, it is that of manufacturing robots. Investment in factories automation is seen as the best way to keep China’s industrial base competitive and cope with the decline in the working population. The chinese industry have come a long way: In 1997, there were only 11 robots installed per 10,000 employees in China, compared to a ratio of tens or even hundreds in the most advanced industrial nations at the time.

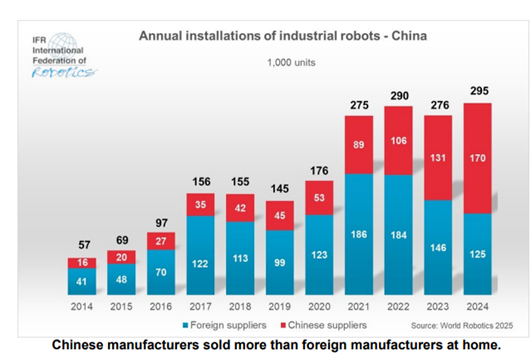

Robot sales have grown significantly worldwide since 2010. They have been driven mainly by Asia, and in particular by China, which has been the world’s largest buyer since 2013. In 2017, with 97 robots per 10,000 employees, China exceeded the global average. By 2024, China reached 470 industrial robots per 10,000 employees. By 2025, 300,000 units have been installed. The increase is therefore continuous: The number of robots has doubled in five years. China is thus climbing onto the podium after South Korea (1,000 robots per 10,000 jobs) and Singapore.

Caption: In 2024, more than 50% of robots installed in China are Chinese. China is still far from achieving such an autonomy in other industries

While industrial robot suppliers have historically been foreign companies – ABB, Hyundai, Fanuc, Kawasaki, Yaskawa, Omron, etc. – Chinese companies such as Siasun, Estun and Kejie are now taking over the market.

This remarkable Chinese success in the robotics industry can be explained by three factors:

- to strengthen themselves, these companies are investing heavily in R&D;

- The technological gap has been partially closed by the acquisition of cutting-edge European companies.

- The cultural enthusiasm of the Chinese population is helping to advance robots that are still far from autonomous.

While China has made robots one of the symbols of its industrial power, Europe seems trapped in a technological paradox: We excel in fundamental research, but we fail to turn our prototypes into commercial successes.

A cultural gap

In Europe, robots are not yet part of everyday life. Unlike in Asia, where demographic decline has been anticipated by state-sponsored “robotophilia”, our societies in Europe often perceive automation as a threat to jobs or a means of surveillance.

This lack of acceptance means that European robots are rarely purchased and therefore much less tested in real-life situations than their Chinese competitors. The risk is that in a few years’ time, the enhanced learning capabilities of Chinese robots will give them such a technological advantage over European companies that it will become impossible to reverse the trend.

A strategic gap

Politically, European public authorities are also too cautious.

First, there is a market problem. Despite a “single market” of 450 million consumers, European standards vary greatly between Member States. The 28th regime proposed by Enrico Letta’s report will not come into effect until 2028 at the earliest.

China, which suffers greatly from fragmentation issues (north-south, urban-rural, Han-ethnic minorities), has introduced regulatory harmonization to enable the development of its businesses.

In terms of investment priorities, the Commission claims to support 120 projects. This pales in comparison to China’s 14th five-year plan, which provides for RMB 1 trillion ($140 billion) in investment over the next 20 years.

Despite these obstacles, European companies are persevering and becoming flagships. But Europe is not defending them well.

The Kuka case: The German flagship bought by China

The takeover of Kuka, the world leader in industrial robotics based in Augsburg, remains the most painful symbol of European naivety in the face of Chinese ambitions. Founded in 1898, the company was the driving force behind German automation, supplying production lines for BMW, Audi and Airbus.

In May 2016, Chinese household appliance giant Midea launched a surprise €4.5 billion takeover bid, offering a 60% premium on the share price. Despite Berlin’s reluctance, no European alternative emerged to counter the bid. The process was completed in 2022 with a delisting, making Kuka 100% Chinese-owned.

What Europe could have done: At the time, the European Union lacked trade defense tools. A European consortium (combining public and industrial capital from companies such as Siemens and ABB) could have been coordinated to keep this strategic know-how under the EU flag. Above all, this takeover revealed the absence of a mechanism for screening foreign direct investment (FDI) – similar to the Committee on Foreign Investment in the USA (CFIUS), which is very active in the United States.

Such a tool was only put in place by the EU in 2019 to protect its critical technologies. Today, Kuka is thriving under Chinese management, but the core of innovation and patents of the German Factory 4.0) now directly fuel the rise of Chinese industry, rather than European sovereignty.

Let us be aware of the risk: Robots will be an essential aid that our businesses and citizens will seize upon as soon as the technology reaches maturity. If we do not change gear, in 10 years’ time our homes, hospitals and warehouses will be populated by Chinese machines whose algorithms, maintenance and data collection we will have no control over.

An existing European ecosystem ready for development

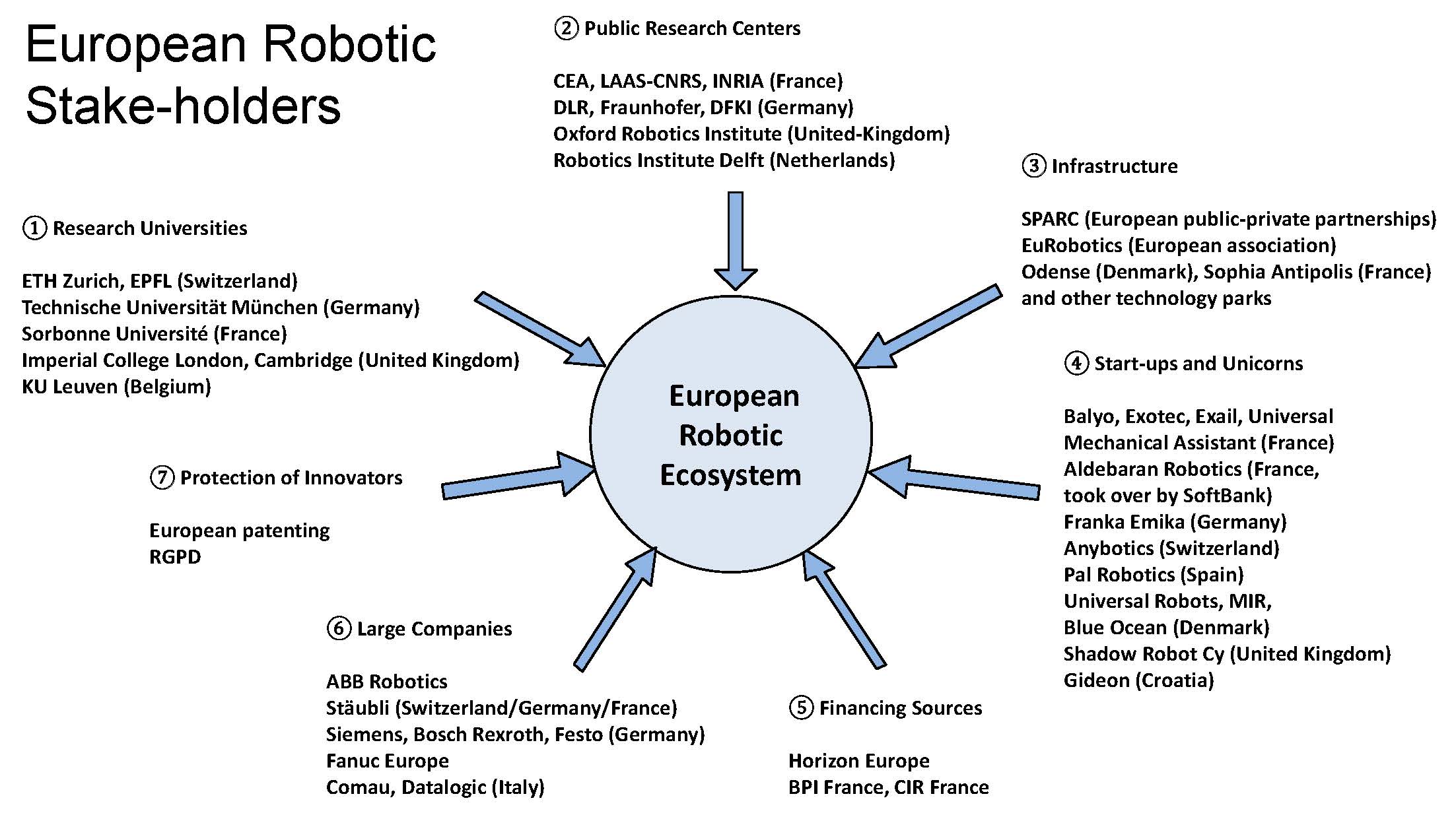

Not all is lost. Europe has some gems that are resisting the Asian onslaught by focusing on added value and security, as illustrated in the diagram below.

Caption: Diagram by Dominique Jolly, inspired by his book The New Threat

To avoid suffering the same fate as the solar panel and software industries, the EU must promote the emergence of a powerful European robotics ecosystem. In concrete terms, this means ensuring that players are present at all stages of the value chain, facilitating their creative interactions, helping to finance them and supporting the market.

Lever 1: Creating a European robotics ecosystem

The biggest gift we are giving China is our regulatory fragmentation. While a Chinese manufacturer produces a single model for its entire country, a European robotics start-up often has to juggle differing national interpretations of the “Machinery” or “Safety” directives.

- Create an additional European company law regime as recommended in Enrico Letta’s report. Europe must create a European Business Code. The idea is not to replace the 27 national laws (a titanic and politically sensitive task), but to offer an optional “28th regime”. A robotics company in Tallinn could then choose to register directly under a single European status without having to recreate legal structures in Madrid or Berlin. This ambition is also being called for by a large number of entrepreneurs through the “EU Inc” initiative.

- Ease the burden on start-ups: The AI Act already provides for regulatory “sandboxes“. These provisions must be used to facilitate the testing and deployment of European robots in real-world conditions.

- Select standards. Europe must select from among the best communication protocols (Open Standards). If a French collaborative robot cannot “talk” to a German machine tool, this creates massive additional integration costs. Let’s use the AI Act to our advantage. Let’s create a European standard for “Trusted Robotics” that guarantees cybersecurity and the protection of industrial data. This would be a criterion for exclusion from public tenders for players who do not comply with our standards of algorithmic transparency.

- Bringing forth European champions: Europe must encourage cross-border mergers and partnerships within Europe to create giants capable of competing with Ubtech or Boston Dynamics. The DG Competition must authorize more European alliances. It cannot repeat its obstacles to the creation of champions, such as its opposition to the alliance between the French (Alstom) and German (Siemens) high-speed trains manufacturers, or to the birth of a French electrical products giant (for which the merger between Schneider and Legrand was aborted). Public investment must focus on large-scale deployment projects. The EU could also make better use of the “projects of common interest” (PIEEC) system to provide financial support for the emergence of a European robotics vertical.

Lever 2: Asset protection (protection of innovation)

- Creation of a European sovereign wealth fund.[SM2.1] Too many European companies are being bought out by their foreign competitors. Yet in a key sector such as robotics, the EU should have a strategic vision of the patents and technologies to be kept under European control. For legal or financial reasons, some European flagships are in bankruptcy. Instead of allowing them to be bought out by China or the United States, a dedicated fund should be set up to save strategic companies. This “rescue” mission could be included in the new “European Competitiveness Fund” provided for in the next European Union budget, amounting to €175 billion over seven years.

- Protection of innovation. China is filing a huge number of patents, some of which are of poor quality, in order to saturate the legal space but also to teach Chinese companies how to file patents. Europe must provide financial support to its SMEs for filing international patents and create a European “IP Box”: A very advantageous tax regime for income from robotics patents, provided that production remains on European soil.

- Alliance strategy: To strengthen the European ecosystem, partnerships can be established with non-European players who do not necessarily wish to ally themselves with the Chinese or Americans. The robotics sector can draw inspiration from the Global Combat Air Program (GCAP) launched in 2025 by the British (BAE Systems), Italians (Leonardo) and Japanese (Mitsubishi) to jointly develop a new fighter jet and its associated drones. Japan, South Korea and Israel all have advanced technical ecosystems. In the field of robotics, an alliance with Japan’s FANUC would pave the way for mutually beneficial cooperation.

Lever 3: Financing and public procurement

- Using public procurement as leverage: Hospitals, postal services and European administrations should prioritize the purchase of “Made in Europe” robotic solutions. This is how China built its champions. Joint transnational orders can multiply the opportunities for these European companies.

- Investing in “Sovereign Robotics”: The robotics sector must be comprehensive. It is necessary to ensure that critical components (sensors, actuators, processors) are produced on European soil to avoid any geopolitical dependence in the event of tension with Beijing.

- Unify sources of funding: The ecosystem remains fragile due to limited funding in fragmented markets: start-ups often have to seek funding in the United States, or worse, be bought out. Europe must open up more solid avenues for these new companies to access capital. In particular, it must help create a single capital market.

Long confined to industry, robots are now moving far beyond the manufacturing sector and into our everyday lives. Against a backdrop of declining birth rates, they are set to play a key role in society. Unsurprisingly, China, supported by its strong government and enormous scale, has invested heavily in this field.

Europe can play its card if it manages to coordinate the efforts of European players without ruling out the possibility of forging new alliances beyond Europe.