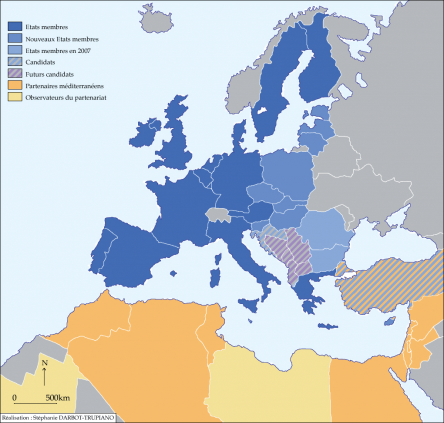

Looking after the neighbourood: responsabilities for EU 25

If the EU is not to drift into offering membership to more and more states around the Mediterranean and across Eurasia, it needs a strategy to organise its neighbourhood.

The EU-25 will be surrounded, from Russia to Morocco, with states economically dependent on access to its markets, concerned about cross-border travel and trade, and anxious for their voices to be heard in EU negotiations. Since 1989 West European governments have successfully extended their established zone of peace, prosperity and security across central and eastern Europe, through the promise of enlargement linked to fulfilment of political, economic and administrative conditions. Promises of membership have already been made to further states in south-eastern Europe.

If the EU is not to drift into offering membership to more and more states around the Mediterranean and across Eurasia, it needs a strategy to organise its neighbourhood, which offers neighbouring states incentives to cooperate and all possible advantages short of membership. Within the current EU there is no consensus on priorities to be given to the eastern or southern neighbours, or on the trade or financial incentives which should be offered. The Commission and the Council Secretariat have floated various proposals in recent months, which the Council of Ministers has received without evident enthusiasm. Many sensitive issues are involved, from border control and migration to further opening of the EU market to imports of agricultural products, textiles and steel; financial incentives would also require a substantial increase in the EU budget allocation for “external action”. Existing policies towards the Mediterranean and the CIS states provide a framework on which to build; but member governments should recognise the limited success of these policies so far, and the resentment and frustration of many of the “partner” states at their continued dependence.

Development of a coherent neighbourhood policy will thus entail substantial costs. But it also offers substantial benefits, in extending prosperity, democracy and security beyond the EU’s borders. The cost of protecting the EU-25 from the spillover of refugees, illegal activities and potential threats from unstable neighbouring states would be much higher. After this enlargement, negotiations within the EU will be preoccupied with internal readjustment. Member government cannot afford, however, to neglect external policy. A strategy towards the EU’s immediate neighbours is the basis for any coherent common foreign policy. That strategy must include an institutional framework for partnership and consultation with the states of the wider Eurasian and Euro-Mediterranean region; a Free Trade Area for Europe and the Mediterranean; and the investment of political leadership, both within the EU and the domestic politics of its member states and across the neighbourhood, required to raise this issue from peripheral to priority status.