Relations avec la Russie : une singularité française

Citer cet article :

Gnesotto, N. 2023. « Relations avec la Russie : une singularité française », Blogpost, Paris: Institut Jacques Delors, 24 mars.

Face à la guerre en Ukraine, la France garde cette posture singulière qui a toujours été la sienne dans les affaires européennes. « La France ne fait jamais rien comme tout le monde », tel est en effet l’agacement immédiat que la politique française suscite chez ses partenaires, qu’il s’agisse de l’Ukraine, de l’Otan, de la puissance américaine, de la Russie, de l’ordre mondial, maintenant comme naguère. D’où la surprise, l’incompréhension, la critique, parfois plus rarement l’admiration qui accompagnent les initiatives diplomatiques françaises.

Quelles sont ces singularités que nos partenaires se plaisent à dénoncer ? La première concerne l’Otan : il est de notoriété publique que Paris n’en est pas un adhérent fanatique. Mais c’est surtout son refus d’un élargissement de l’Otan, au sommet de Bucarest de 2008, qui fait débat : la France et l’Allemagne y voyaient en effet une ligne rouge russe qu’il valait mieux ne pas franchir. Or personne ne saura jamais si l’extension de l’Otan à l’Ukraine en 2008 l’aurait sauvée de l’agression russe quinze ans plus tard, en 2022, ou si cette décision aurait entrainé la guerre avec la Russie quinze ans plus tôt. Ceux qui pensent qu’à l’époque Poutine était un dirigeant réaliste, différent du revanchard sanguinaire qu’il est aujourd’hui, devraient apprécier que l’Otan ait évité, grâce au blocage français, de provoquer dangereusement la Russie de l’époque. Ceux qui sont à l’inverse persuadés que Poutine a toujours été le même despote impérialiste devraient également se féliciter que la prudence de l’OTAN ne lui ait pas donné le prétexte idéal pour envahir l’Ukraine en 2008, car ce pays récemment libéré du joug soviétique (août 1991), était sans doute beaucoup plus fragile et moins prêt à la résistance qu’il ne l’est aujourd’hui.

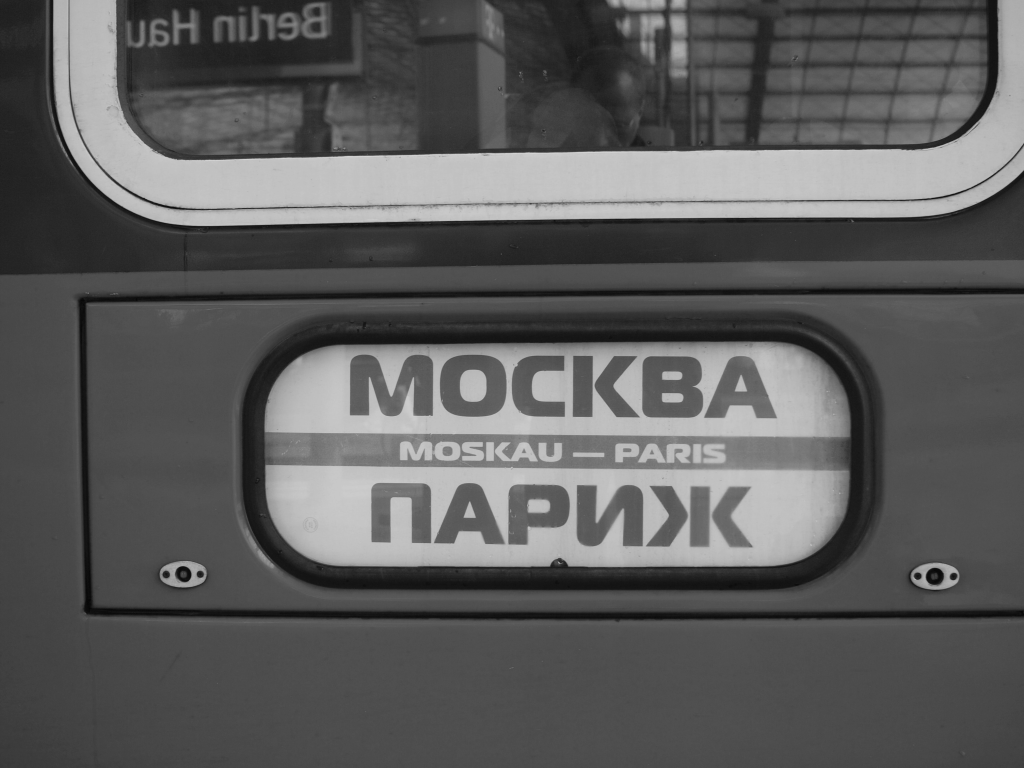

Le second reproche fait à la France concerne sa vision de la Russie comme une grande puissance et son obsession du dialogue Paris-Moscou. Emmanuel Macron endosse en effet l’héritage de tous ses prédécesseurs, préoccupés à des degrés divers par la construction d’une architecture de sécurité européenne commune avec la Russie. Quelques mois avant l’agression russe, il proposait encore au Conseil européen de juin 2021 d’en faire une priorité politique. Dans les semaines précédant l’invasion et longtemps encore après, il multiplia les appels téléphoniques à Poutine, parfois de façon très exhibitionniste, dans l’objectif de maintenir une porte de dialogue ouverte vers des négociations. L’une de ses déclarations les plus controversées intervint en juin 2022, quand il expliqua que Poutine faisait une erreur historique avec cette guerre mais qu’il ne fallait pas « humilier la Russie ». Alors que l’Europe entière se situait dans l’émotion et le soutien sans réserve à Kiev, le président français, avec son approche historique (l’Allemagne au traité de Versailles) et sa realpolitik de long terme, choqua. « Les appels à éviter d’humilier la Russie ne peuvent qu’humilier la France ou tout autre pays », commenta le chef de la diplomatie ukrainienne, suivi par nombre de ses collègues baltes et est-européens. Il est vrai qu’à l’heure des images insupportables des atrocités commises par les Russes contre des enfants et des civils ukrainiens, les propos du chef de l’Etat étaient plus que maladroits.

Le président français comprit le message et se rallia au langage commun des Occidentaux à partir de septembre dernier. A la conférence annuelle de sécurité Munich, en février 2023, il rassura tout le monde en disant souhaiter « la victoire de l’Ukraine » et « la défaite de la Russie ». Mais il ne renonça pas pour autant à sa vision stratégique du long terme : « Je ne pense pas, comme certains, qu’il faut défaire la Russie totalement, l’attaquer sur son sol. Ces observateurs veulent avant tout écraser la Russie. Cela n’a jamais été la position de la France et cela ne le sera jamais ».

Est-ce l’erreur de trop ? Celle qui fait de la singularité française, non pas un atout mais un handicap ? La réponse est à mes yeux négative, surtout si l’on considère cruciales pour l’avenir les questions suivantes : 1) Est-ce une erreur, comme le fait la France, de distinguer entre Poutine, criminel de guerre, et la Russie, puissance européenne pour l’éternité ? 2) Est-il stupide de rappeler que l’on ne peut pas détruire une puissance dotée de l’arme nucléaire ? 3) Est-il réaliste d’attendre l’installation d’un régime démocratique à Moscou pour accepter de reprendre une relation avec la Russie ? 4) N’est-il pas nécessaire de tenter d’articuler une vision de court terme (la défaite de Poutine est souhaitable) avec une stratégie à long terme (la relation avec la Russie est inévitable) ?