Tomorrow, a Europe of Six?

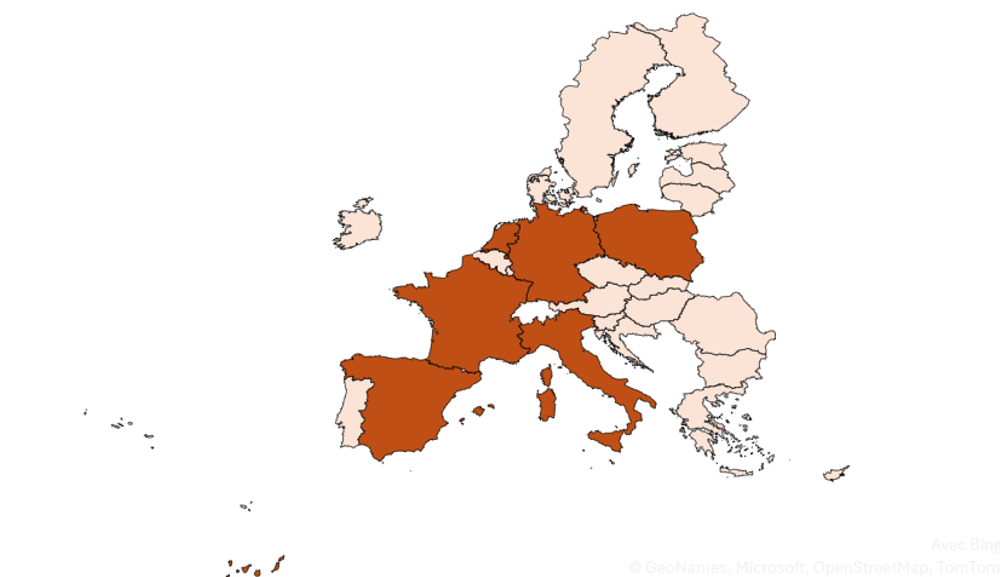

On 27 January, German Finance Minister Lars Klingbeil, a Social Democrat, dropped a bombshell on the European stage. He called for the creation of a two-speed Europe, proposing to set up a select club within the 27-member EU comprising six countries: France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Poland and the Netherlands. The idea of a multi-speed Europe is not new and seems likely to respond to many of the current difficulties. But its implementation remains both complex and highly uncertain

The deadlock in the EU-27

First of all, there is unfortunately little doubt about the limitations, and even the deadlock, of the EU-27. The EU is clearly incapable of making decisions quickly and forcefully enough to defend the interests and values of the Union in the hostile context created by Donald Trump on the one hand and Vladimir Putin allied with Xi Jinping on the other. Similarly, it does not seem capable of taking the necessary measures to make up for the considerable lag in key technologies for the future and to quickly correct its excessive dependence on both China and the United States in most areas that are essential to its economy.

Even though qualified majority voting has become the rule in most areas of EU action, unanimity continues to be required on several issues crucial to its future: taxation, foreign and security policy, the EU budget and, of course, the revision of the Treaties themselves, and therefore changes to internal rules.

Under these conditions, it remains very difficult to limit the social and fiscal dumping that undermines the cohesion of the Union, to build a common defence and respond in a timely manner to external aggression, or to acquire the resources necessary to pursue the active industrial policy, essential to catch up with the EU’s technological lag.

Successive enlargements have paralysed the Union

These long-standing structural difficulties have been exacerbated by successive enlargements, which have gradually paralysed structures such as the Council and the Commission, which were originally designed to function with six countries. These bodies have remained virtually unchanged since then, even though the number of EU members has more than quadrupled. As a result, the Council can no longer really be a forum for debate: once each country’s representative has spoken for five minutes on a subject, two hours and 15 minutes have passed. As for the Commission, the subdivision of its areas of responsibility into 27 means that there is considerable overlap and that no Commissioner can take significant measures in the various areas of EU action. Ultimately, only the Presidency of the Commission counts, but this excessive concentration of power slows down and paralyses the work of this institution.

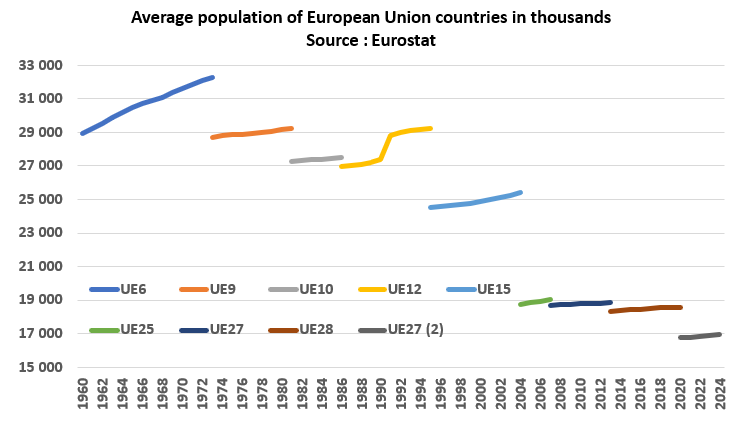

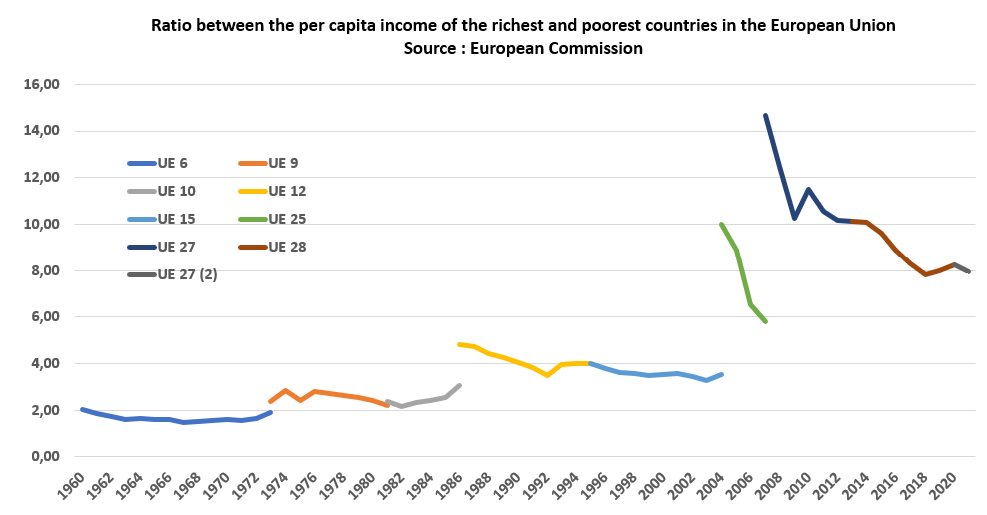

Beyond their purely numerical dimension, successive enlargements have mainly consisted of bringing small countries into the Union. In the days of the Europe of Six, the average population of a Union country was 32 million. In the Europe of 27, it has fallen to 17 million, almost half. Each enlargement has lowered this average. At the same time, these enlargements have also increased internal inequalities within the Union. In the Europe of Six, the ratio between the GDP per capita of the richest country and that of the poorest country was 2. In the Europe of 27, it is now 8.

The domination of small countries at the expense of large ones

However, the Union’s political system actually favours small countries over large ones: each state, regardless of its size, has a place in the Council and a seat in the Commission. Even the European Parliament does not allow for fair representation of European citizens: a Maltese MEP represents 96,000 inhabitants, while a German MEP represents 872,000, almost ten times as many. Admittedly, qualified majority voting takes this population dimension into account, but such votes are in fact very rare and consensus is still most often sought within the Council.

Beyond this issue of the structural over-representation of small countries, their dominance within the European Union has a negative impact on common policies. Small countries suffer much less than large countries from internal social and fiscal dumping, which weakens the European Union’s economy and undermines its social and political cohesion.

For a small country, the ratio of exports of goods and services to GDP is almost always much higher than for a large country where domestic demand weighs heavily on its economy. When a small country decides to lower its labour costs, or to curb their rise, in order to improve its cost competitiveness vis-à-vis its European neighbours, it loses domestic demand because these costs are also income for its inhabitants. However, this domestic demand is limited and the gains made in exports can quite easily offset its decline and boost economic activity. When a large country wants or is forced to pursue the same policy, it is bound to lose out: it cannot compensate for the loss in domestic demand through additional exports.

The same logic applies to fiscal dumping: when a small country reduces taxation on the income and wealth of the very rich and on corporate profits, it certainly loses domestic tax revenue, but this loss can be fairly easily offset by the arrival of additional wealthy individuals and businesses. When a large country is forced to follow suit to prevent all its wealthy individuals and companies from moving to these tax havens, it inevitably loses out in terms of tax revenue. And its deficits and public debt increase.

Small countries are blocking European defence and industrial policy

In short, social and fiscal dumping within the EU weakens domestic demand and therefore the economy of the entire Union, while exacerbating the difficulties of European countries’ public finances and contributing to setting Europeans against each other. But small countries suffer much less than large ones. They even benefit from it, as we have seen in recent decades with Luxembourg and Ireland in particular. They therefore have no interest in correcting this major flaw in the EU, unlike the large countries.

Similarly, small countries generally do not have “national champions”, i.e. multinationals capable of operating on a global scale. Their economies are most often dominated in almost all sectors by foreign multinationals, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe. Whether these multinationals are French, German, Chinese or American makes little difference to them.

In fact, the opposite is sometimes true: multinationals from Western Europe can provoke more negative reactions within these societies than those from further afield, due to a widespread feeling of ‘colonisation’ by Western Europe after the fall of the Berlin Wall. These small countries are therefore not calling for a more active industrial policy that better protects European companies and the EU’s internal market.

As for their defence and security, given their size, these small countries know that they do not have the means to ensure it and that they must rely on larger countries for this. But all things considered, many of them prefer to continue to rely on the United States for this purpose rather than on Germany, which has left very bad memories in the region, or on a distant France that is clearly indifferent to the fate of Eastern Europe. Unless they prefer to seek Finnish-style arrangements with Vladimir Putin’s Russia…

The Europe of Six makes sense, but…

In short, the institutional structure of the European Union favours small countries at the expense of large ones. Moreover, the numerical dominance of these small countries within the Europe of 27 prevents these dysfunctions from being corrected and the policies from being adopted, that are essential to respond to the aggression of Trump’s United States and the alliance between Xi Jinping’s China and Putin’s Russia, or to increase Europe’s strategic autonomy in key areas.

In such a context, the approach proposed by Lars Klingbeil – bringing together the six largest countries in the Union to move forward together – makes sense. These six countries – France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Poland and the Netherlands – together represent only 22% of the EU’s member states, but they account for 70% of the EU’s population and 72% of its GDP. They therefore form a critical mass which, if it moves together, should be able to bring the rest of the EU along with it.

But between what makes sense on paper and the practical implementation of such an idea, there are major obstacles. First of all, there is the question of the internal cohesion of this group. Between Spanish socialist Pedro Sanchez and Italian far-right leader Giorgia Meloni, there are not necessarily many points of agreement. And even between Emmanuel Macron’s France and Friedrich Merz’s Germany, Europe has been echoing in recent months with their multiple disagreements on the Future Combat Air System (FCAS), the confiscation of frozen Russian assets, Eurobonds, and more.

What could such a group of countries agree on? Despite all the difficulties mentioned, would it be possible to make progress in this framework on issues such as tax harmonisation, defence policy and defence industries, digital policy, financial market unification, climate policy, social harmonisation or even the issuance of common debt to finance efforts in all these areas? It seems very difficult, but it would obviously be wonderful.

An alternative to the 27-member Union?

But even if such a club were to be formed and agree on this or that issue, its troubles would not be over. First of all, although these six countries carry considerable weight demographically and economically, they could not single-handedly change the rules of the game across Europe: a qualified majority in the Council of the European Union requires votes representing 65% of the European population (which the club of six would achieve) but also 55% of the countries of the Union, i.e. 15 countries at present. They would therefore need to find at least nine allies among the smaller countries of the Union on each issue.

Furthermore, the club of six could not on its own form an ‘enhanced cooperation’ as provided for in the European Treaties, which is precisely intended to allow the creation of possible European ‘vanguards’ in various fields. This requires the participation of at least nine Member States and the agreement of the Council by a qualified majority (see previous point) and even its unanimous agreement for areas relating to defence or foreign policy.

However, it would probably not be very difficult to bring Portugal, Belgium and another state on board such a project if necessary. The States participating in enhanced cooperation may, in particular, decide within their group to waive the unanimity rule and adopt qualified majority voting on issues such as taxation or defence, where this still applies to all 27 Member States. This would be a major step forward.

However, if strong measures are taken within such a restricted framework, they may quickly become difficult to reconcile with the maintenance of a single market of 27 Member States. If this vanguard were to agree, for example, on upward harmonisation of taxation on the income and wealth of the very rich and on corporate profits, but capital flows remained free to Cyprus, Malta, Luxembourg or Ireland, the situation would undoubtedly become difficult for the club of six.

If the aim is no longer to operate within the framework of the EU institutions but to build a new institutional framework outside the EU, with, for example, a specific treaty on European defence, difficulties are bound to arise quickly between this club of six and the 27-member Union, with this vanguard potentially accelerating the crisis and possibly bringing about the end of the EU.

In short, this format of a Europe of 6 makes sense in principle, but beyond the concept, everything remains to be built. And there are many pitfalls along the way. Assuming that this club of 6 manages to consolidate itself, the direction it could take remains very open at this stage. One thing is already clear, however: such a project is only likely to prosper and be useful for the future of Europe if the far right does not win in France next year.