2030 climate targets: a political challenge rather than a technical one

This blogpost is an expanded version of an oped published in Les Echos on 2 July 2025 and was translated through IA. Please refer to the original French version for exact quotes or contact the author.

In Europe, stating that the European Green Deal is no longer bankable is an understatement. Calls for a “regulatory pause“[1] , a deregulatory policy disguised under a simplification agenda[2] , the unravelling of previously set climate targets for fear of an ecological “backlash” – there are many examples that illustrate this reality.

In the midst of this political morass, the latest assessment published by the European Commission could be a welcome ray of light. It estimates that the European Union (EU) will be able to achieve a 54% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, just 1% below the target of 55% compared to 1990 levels. To reach this conclusion, the European executive assessed the National Energy-Climate Plans of twenty-four of the Member States (with the exception of Belgium, Estonia and Poland), which list the actions and public policies that each country intends to undertake to help achieve its climate objectives. This is a optimistic analysis, that needs to be tempered for at least three political reasons.

Pessimism of reason

Firstly, how much credit can really be given to the commitments made by the Member States as part of this Europe-wide planning exercise? The fulfilment, as well as the content, of the stated climate commitments remains intrinsically linked to the political coloring of the Head of state or governments in power within each country. Whether as a result of an election[3], budgetary constraints or for any other reason, a redefinition of political priorities in the energy field – as is currently the case in France, for example – could lead to a downgrading of the ambitions initially announced to the European Commission. Ultimately, this calls into question the Commission’s ability to ensure that these commitments are truly respected, using the legal tools at its disposal, something it has so far refused to do. For the Commission, there is a risk of inflaming the Member States a little more, at a time when its political capital on the climate issue is already severely depleted.

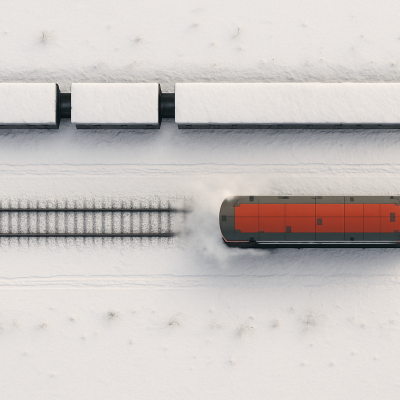

Secondly, the Commission’s analysis is based on a double conditionality, namely that the Green Deal must be implemented in accordance with the agreed European legislation, and that it must also be implemented diligently. To put it another way, for the 54% reduction in emissions to be effective, the European laws and objectives as voted during the previous term of office would have to be applied on time within the 27 Member States. However, in the transport sector alone, the main source of emissions at European level, the recent backpedaling for car manufacturers in terms of rules on CO emissions2, the expected backpedaling concerning the end of sales of new internal combustion vehicles in 2035, and the delay by several Member States (including France) in transposing the extension of the European carbon market to the transport sector (and to the building and small industry sectors) illustrate the shortcoming of the European Commission’s analysis which did not take account of the current political reality.

Thirdly, the plans submitted by the capitals do not detail either the amounts or the way in which fundings (public and private) will be mobilized in order to complete this ecological transition. At a time when the EU has a climate investment deficit of almost 2% of European GDP (i.e. around 400 billion euros), the decarbonisation bank alone, which is supposed to mobilize 100 billion euros over ten years, will be insufficient. Added to this is the expiry, at the end of 2026, of the funds from the Recovery and Resilience Facility, 37% of which were dedicated to the climate, i.e. around €275 billion. Discussions on the next European multiannual budget (2028-2034) will also begin in the summer. A status quo in terms of the total amount of the latter’s expenditure (30%, or around €360 billion) allocated to climate-related objectives would be a decent outcome, given the multiplication of priorities at European level, such as the security and defence or competitiveness agendas.

So, while the objectives remain technically feasible, subject to adjustments in the transport, buildings and agriculture sectors, achieving our climate targets for 2030 seems, as things stand, politically difficult to reach, since it is intrinsically based on the increasingly inadequate voluntarism of Member States.

Optimism of will

Yet abandoning the European Green Deal would be nothing less than a betrayal of the democratic promise made following the 2019 European elections. A promise to disillusioned young people who, through an unprecedented mobilization drive, democratically legitimized the adoption of more than sixty sectoral laws, the benefits of which should materialise over the next few years. As the energy price crisis has shown[4] , speeding up the decarbonisation of our society is a key factor in our resilience to the geo-economic shocks that punctuate the world. The International Energy Agency has put a figure of 100 billion euros on the savings made by European electricity consumers between 2021 and 2023 thanks to the additional deployment of renewable energies.

As demonstrated above, the success of the transition now depends on the ability of our decision-makers not to give in to the populist sirens that urge them to renounce all or part of their political heritage. It also depends on the mobilization of all the driving forces. Those able to articulate a discourse that will enable us to take the issue of decarbonizing our economy beyond mere sustainability issues.

[1] Nguyen, P.-V. “Pacte vert: vers une ” pause réglementaire européenne ” “, Décryptage, Institut Jacques Delors, January 2024.

[2] Nguyen, P.-V. ” L’énergie, bien plus qu’un marché“, Blogpost, Institut Jacques Delors, June 2025.

[3] Thalberg K., Defard C., Chopin T., Barbas A. & Kerneïs K. “The European Green Deal in the face of rising radical right-wing populism“, Policy Paper n. 296, Paris: Jacques Delors Institute, January 2024.

[4] Nguyen, P-V., Pellerin-Carlin, T. “Flambée des prix de l’énergie en Europe“, Institut Jacques Delors, 6 October 2021.