Brexit : the worst is yet to come!

Blogpost based on an oped published in Le Monde, 31 January 2019 by Elvire Fabry, Senior Research Fellow, Jacques Delors Institute. Translation from French by Barbara Banks.

It will have taken three and a half years and a major political crisis in Britain to finally make the UK’s exit from the European Union official. Yet 31 January 2020 only marks the UK’s political departure: from that date on, it no longer takes part in decisions made on a European level. The country’s legal departure still lies ahead and will only fully come into force after the unravelling of some 750 agreements which connect it with the European bloc. The withdrawal agreement only guarantees citizens’ rights, peace in Ireland and the settlement of financial commitments. For the rest, just as planes cannot be stopped in mid-air, we cannot be satisfied with a legal vacuum. Beyond the stakes of maximum economic cost with a return to border checks and customs duties negotiated with the WTO, it is the daily lives of British citizens and many Europeans that will be disrupted by the uncertainties surrounding the blank slate in many areas (data transfers, energy, transportation, security, fisheries, etc.).

Negotiators are facing a colossal and unfeasible task in the eleven-month transition period which Boris Johnson intends to stick to, with the final withdrawal scheduled for the end of the year. It will not be long before the question of extending the transition period will be raised again. In the meantime, negotiators are drawing up priority-setting and sequencing strategies to maintain the links between the different phases. Yet for now, the most decisive challenge of this negotiation must be fully defined: the need to guarantee the conditions for equal competition between the United Kingdom and the European Union (the famous level playing field), an absolute prerequisite for maintaining open trade.

Admittedly, Europeans intend to uphold the closest possible bilateral relationship, notably to preserve a good security and defence cooperation. However, there is a much more existential challenge for the EU-27: to preserve the integrity of the “regulatory ecosystem” which forms the basis of the Single Market. During the withdrawal negotiations, Europeans succeeded in “constitutionalising” the indivisibility of the four freedoms of movement (people, goods, services and capital). At the moment, the priority is to establish that rules on social or environmental issues, or on the restriction of state support, cannot be separated and considered as optional without giving rise to regulatory dumping and a distortion of competition.

To date, the challenge is a major negotiation priority for the European Commission, against a backdrop of increasing competitive distortions caused by emerging economies and new economic powers such as China. By maintaining a lower level of regulation, the latter are conducting regulatory dumping on European companies in particular. While, in this respect, Europeans are tackling Chinese state support or are beginning to apply border adjustment mechanisms to prevent carbon leakage, as regards Brexit, they can only keep an eye on Boris Johnson’s aspirations towards regulatory divergence.

To date, the challenge is a major negotiation priority for the European Commission, against a backdrop of increasing competitive distortions caused by emerging economies and new economic powers such as China. By maintaining a lower level of regulation, the latter are conducting regulatory dumping on European companies in particular. While, in this respect, Europeans are tackling Chinese state support or are beginning to apply border adjustment mechanisms to prevent carbon leakage, as regards Brexit, they can only keep an eye on Boris Johnson’s aspirations towards regulatory divergence.

Negotiators are less willing to make concessions to their long-standing British partner as the final agreement will set precedents for other third countries. For the trade component alone, the European Union must comply with the “most favoured nation” clause which applies to most preferential agreements that it has signed worldwide and which provides that any commercial advantage granted to one of these countries must be extended to the other countries with which it has an agreement.

On 31 January 2020, Brexit therefore became a tangible reality, which celebrates taking back control of full sovereignty without a clear strategy of commitment on the global economic stage. We are now waiting for the British government to clarify its intentions regarding regulatory autonomy.

Boris Johnson enjoys great political leeway as, in addition to the clear majority he obtained in the House of Commons last December, he made sure that the revised withdrawal agreement would limit the powers of parliamentary scrutiny over the future negotiations.

He will likely first attempt to call for a distancing from European regulations in a differentiated approach as the political cost of divergence from European social and environmental standards would be too great for the Conservative Party. If he were to focus on state support, this is where the risk of distortion is the greatest and Europeans’ tolerance the weakest. We would then witness the stark reality of bilateral confrontation.

The deep desire of the British is probably even more to be able to exercise their newfound regulatory independence without necessarily wanting to diverge from European regulations, which is like trying to square the circle.

The deep desire of the British is probably even more to be able to exercise their newfound regulatory independence without necessarily wanting to diverge from European regulations, which is like trying to square the circle.

We should not rule out the possibility that, like the way he did for the general elections, Johnson may ultimately use the pressure of a short transition period and a risk of no deal at the end of 2020, to weigh in on regulatory alignment. If such a scenario were to occur, it would be more due to Brexit fatigue rather than British public opinion being realistic about the impacts of Brexit’s economic cost.

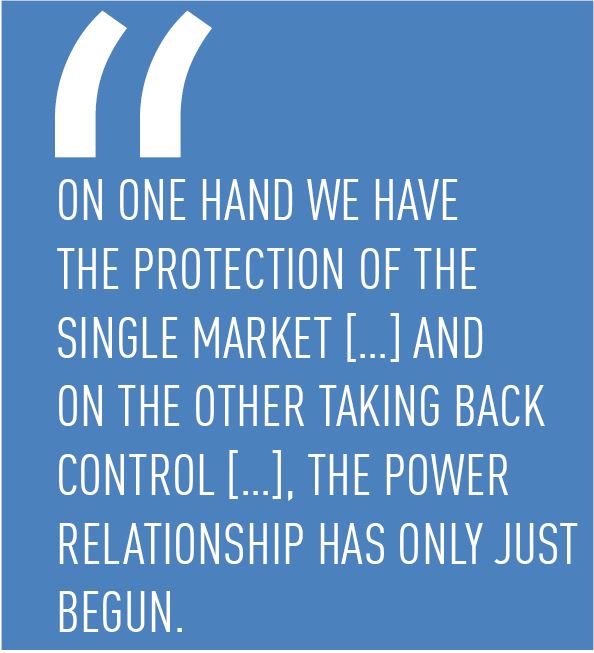

As we have seen, on one hand we have the protection of the Single Market and the legal framework and on the other taking back control and the desire to undertake a political negotiation. The power relationship has only just begun and the worst is yet to come.