[FR] Enlargement: Breaking down the wall of rejection

This publication is available in french.

This article, published in the JDD on 3 November 2019, gives the floor to Sébastien Maillard, Director of the Institut Jacques Delors.

If there is one European expression that exasperates the British and helped motivate Brexit, it is the goal of an “ever closer union” enshrined in the preamble of the EU’s founding treaties. What unsettles the French, on the other hand, is the prospect of an ever-wider Union, opened up by the numerous accession requests, such as those from Albania and North Macedonia.

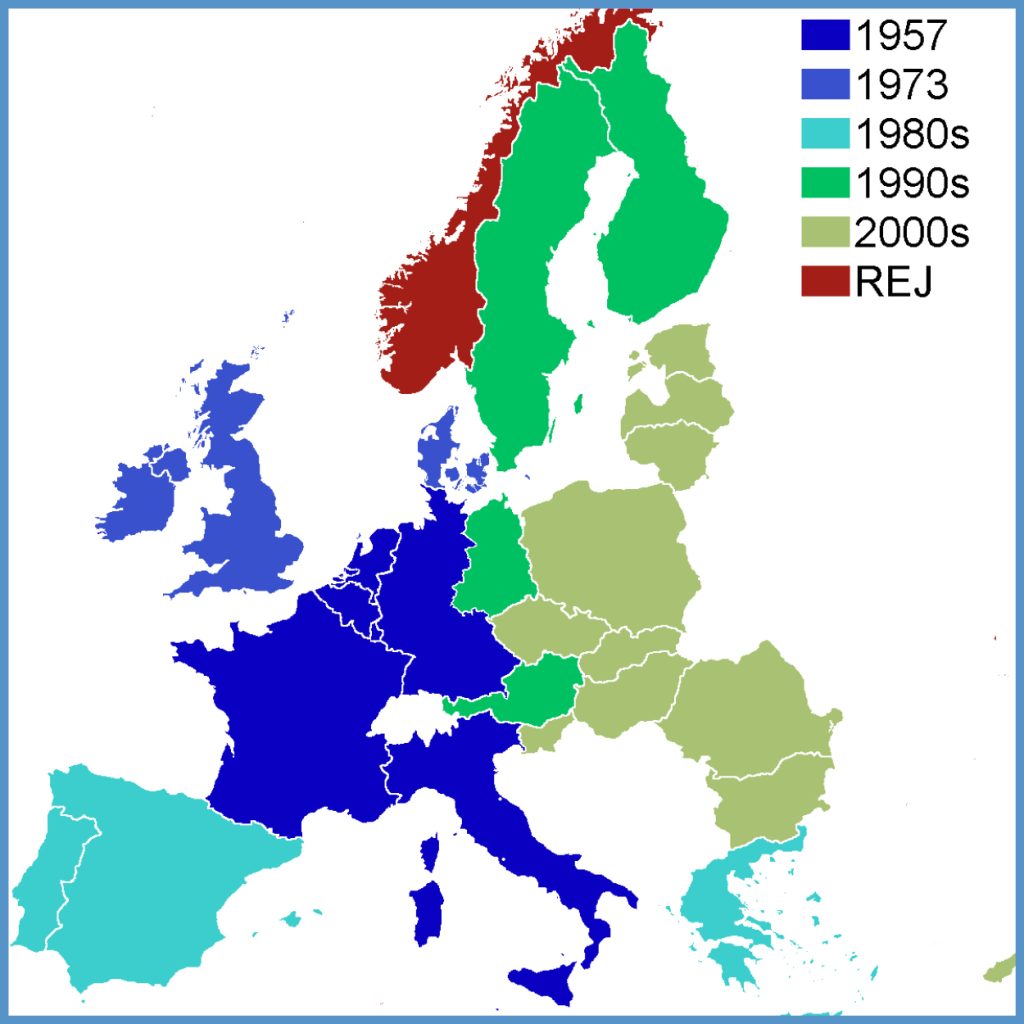

The fall of the Berlin Wall, 30 years ago, suddenly brought this prospect of a wider Union across the continent much closer. That expansion is inherent to the European project, from the very beginning. Let us remember: the 1950 Schuman Declaration aimed at “the coming together of the nations of Europe” and was “open to all countries.” In this sense, enlargement is not the dilution of the European project but rather its full realization.

Yet the French have been told the exact opposite narrative. Where the countries freed from communist rule rejoiced at returning to the European family—seeing EU membership as intertwined with their regained national sovereignty—we in France saw only impoverished foreigners taking our jobs, offshoring, and posted workers. Where Gorbachev spoke of a “common European home,” John Paul II of a Europe breathing with “two lungs,” and Jacques Delors of “East-West reconciliation” and a “greater Europe,” we moved forward reluctantly, as if the European project were slipping from our grasp. With the fall of the Wall also fell a certain French vision of Europe.

Since then, enlargement has been poorly digested in France, carried out behind closed doors. There was no educational effort, no political explanation, no media coverage. Nostalgic for the good old days of the Twelve, we see the EU of 28 as nothing but dysfunction. Through this narrow lens, every new accession—no matter how distant or conditional—is fundamentally unpopular.

Without hiding the problems, we must look at enlargement from different angles to grasp its full significance. Not only does it not contradict deeper integration within the Union, but it is also not the sole cause of its dysfunction. These arise at least as much—if not more—from the underperformance of the Franco-German engine and repeated British vetoes, culminating in the prolonged impact of Brexit.

More fundamentally, enlargement must be presented not as something suffered, but as something chosen. It is a decision. Every accession requires the unanimous consent of existing members. Every EU member was admitted because we democratically agreed to it. Our deputies and senators ratified each accession treaty—Croatia’s in 2013, for instance—on behalf of the French people, who even voted by referendum in 1972 for the United Kingdom to join.

We can also frame the question of enlargement in reverse. What if these countries had never joined? The violent period of instability experienced by the former Yugoslavia after its breakup contrasts with the stability that the prospect of EU membership brought to Central Europe. This stability on our doorstep, and the relative prosperity it brings, is clearly in our own best interest.

The question also looks to the conditional future: What if they never joined? At a time when other powers, like China, are investing in the Balkans, and Russia is destabilizing neighbors left outside the EU, the Union must consider the geostrategic value of enlargement in this region.

In this regard—a dimension dear to France—a Europe of power is inherently linked to an enlarged Europe. Faced with multiple threats and rival powers, the EU must be large enough to carry weight. By contrast, Brexit inevitably marks a retreat of Europe on the global stage.

Nevertheless, enlargement does not preclude differentiation. Member states can choose to move further in integration than others, without exclusion. The eurozone and the Schengen Area are examples of differentiated integration—an approach that is now essential in areas like migration and defense. What cannot be subject to differentiation, however, is the respect for our common values as set out in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, and on which strict vigilance is more necessary than ever.

That said, enlargement is not “endless,” as is too often claimed. The idea of Turkey’s entry poisoned this debate for too long, and the authoritarian turn of Erdoğan’s regime should now force a decision.

Although enlargement is part of the Union’s original purpose, it should never be automatic. Emmanuel Macron has highlighted the inertia of a process that is overly legalistic. But any revision of the enlargement process, as called for by Paris, cannot avoid a calm explanation to the French people about why it matters, and a renewed narrative. The EU’s “absorption capacity”—a criterion put forward by France in 2006—requires that public opinion in member states be better informed and involved from the outset. Citizens must see meaning and benefit in it. In short, enlargement should also, in its own way, be participatory. Rather than a veto, it deserves a debate. Otherwise, we risk the rise of a new wall—of misunderstanding, mistrust, and rejection.

Sébastien Maillard

Director of the Jacques Delors Institute