[FR] Illiberal Democracy or Majoritarian Authoritarianism? Contribution to the analysis of populisms in Europe

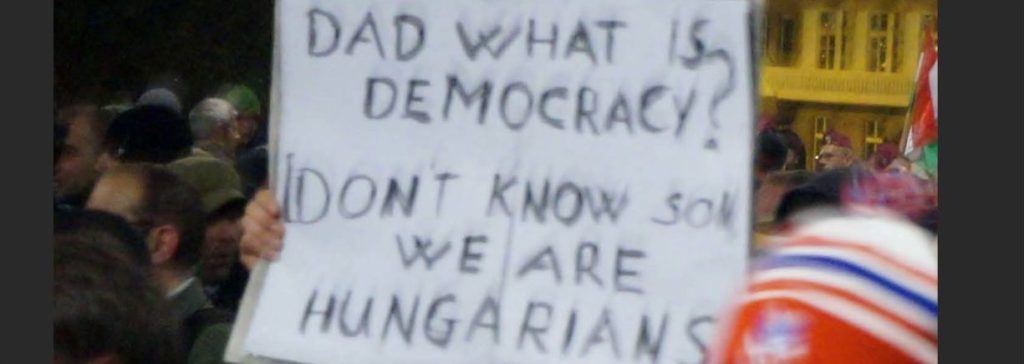

The crisis of the European project is related to the crisis of liberal democracies, even if the latter crisis does not concern Europe specifically, as demonstrated by Donald Trump in the USA and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil. However, in recent years, liberal democracy has been strongly called into question in Europe under pressure from national, populist and extremist political forces which claim the name “illiberal democracy”, as is currently the case in Hungary with Viktor Orbán’s regime. One of the fundamental problems of the current political climate in Europe is that the rise in populism comes with a dissociation of the two components of constitutional and liberal democracy that have been the foundation of our democracies since the end of the Second World War. From this standpoint, there is an absolute need to reconsider the links between democracy and political liberalism.

The democratic political regime is naturally based on the combination of people’s sovereignty and the majority principle under which the political choices made by citizens are the result of decisions taken by the majority. However, institutions upon which a direct or indirect democratic legitimacy is conferred do not have a monopoly over the public good. Being subject to electoral sanctions may lead governments and MPs to adopt short-term decisions which run counter to the general interest. This is the basic principle of liberal constitutionalism which has been at the core of our democracies since the end of the Second World War: independent institutions must act as a safeguard against the excesses of a government, even if it is democratically elected, in order to protect the minority from the risks of “tyranny of the majority”.

With the “rise of majority regimes”, the consequences of globalisation and the impact of the migration crisis may lead to “majorities” which feel threatened socially, economically and/or culturally to want to consolidate their power, and in doing so exclude minorities and their rights. The fear of finding themselves in a minority (cf. fears of the “Great Replacement”) may lead a group to want to secure a majority position restricting the “people” to their group as much as possible. In addition, elections are no longer used in certain countries to change government but rather to change regime and promote the shift to more authoritarian regimes. Ultimately, the illiberal democracy approach implies giving limitless power to the “majority”, which becomes increasingly difficult to define, embodied by a charismatic leader claiming to have the monopoly of the “people’s” general will which is nevertheless so complex to identify.

Stripped of its principle of power limitation and moderation, the illiberal democracy is in practice a smokescreen that conceals the shift towards a “majority authoritarianism”, the characteristics of which are increasingly clear: the desire of authoritarian leaders to avoid their power being questioned, a tight control of politics by reducing the uncertainty of electoral competition, the weakening of opposition forces so as to control the State apparatus more effectively, intervention in the media to control information and communication and the reduction of academic freedom. It is then possible to question the alleged democratic nature of populist and illiberal authoritarianism which is basically characterised by “anti-pluralism”. The populist criticism of the elites systematically comes with the claim to have the monopoly of the expression of the “real” people’s will, and yet citizens’ freedom requires that they are not held hostage before it is expressed and democracy implies the pluralism at the centre of political liberalism.