Policy paper 288

Europe’s response to the Sino-American rivalry

Quote this article :

Fabry, E. 2023. «Europe’s response to the Sino-American rivalry», Policy paper n°288, February 2023.

Introduction

Back in 2019, there still was much speculation about whether Washington intended to “reform, leave, or dismantle the World Trade Organisation (WTO)?”1 This uncertainty arose at a time when the US was blocking the appointment of new judges and effectively throwing a wrench into the smooth functioning of the WTO’s Appellate Body. The answer has become clearer since.

The distortions of competition caused by Chinese state capitalism create systemic imbalances of such magnitude within the liberal market economy that the US has decided to circumvent some multilateral rules on national security grounds. Washington has adopted coercive measures and an industrial strategy echoing China’s approach based on massive subsidies and domestic content requirements. In a game of tit-for-tat, Washington and Beijing keep exchanging one aggressive announcement after the other. The race for technological leadership is accelerating alongside a reshuffling of globalisation that could equally result in the coexistence of rival blocs, or in an escalation of retaliatory measures and the fragmentation of global value chains.

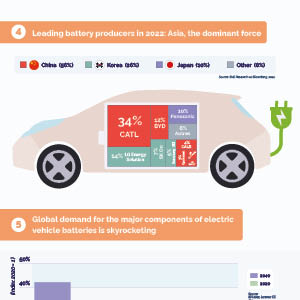

The rest of the world has little choice but to adapt to this global environment that is becoming increasingly marked by conflict. Some American initiatives that take aim at China also have an impact on third countries, such as the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), a colossal state aid plan adopted by US lawmakers in August 2022. The IRA aims to spur the innovation and production of green technologies in the US in order to achieve the goal of carbon neutrality, while reducing dependence on Chinese technology and curbing the flow of critical US technologies to China to slow down its economy. Federal funding will likely end up exceeding the advertised price tag of $369 billion (€345 billion) planned over ten years, given that not all financing projects have ceilings. Many countries have raised concerns over the public aid package—concerns that are heightened by America’s unlimited capacity for subsidies afforded by the US dollar. The IRA is strengthened by local content requirements that distort competition between US-based companies and those located elsewhere [2].

Europe must act to prevent European investment from being diverted to the United States, where the cost of energy is already much lower, without triggering a fullfledged subsidy race among EU Member States that would undermine the rules of fair competition upon which the Single Market is built.

The stakes, however, are much broader than just taking measures to respond to the IRA. Europe must ensure access to technologies that will deeply transform our economies and societies. These are highly promising growth sectors in which Europe would be mistaken not to position itself by developing its own capacities for innovation and production. Crucially, access to these technologies will no longer be based on trust in an open global market, as it becomes increasingly difficult to navigate geopolitically-driven export restrictions. Europe is taking active steps to reduce its strategic dependencies, especially on the import of goods whose production is highly concentrated in China. However, it must also prepare for a new risk of concentration of technological innovation and production, which could create new dependencies on the two countries leading this technological race.

This paper does not delve into the details of the IRA or the Green Deal Industrial Plan proposed by the European Commission on February 1, 2023 [3]; instead, it evaluates the implications of the changing nature of globalisation to situate the European debate at the appropriate strategic level. The impact of Washington’s priority given to national security (I) and the risk of an escalation of export restrictions (II) call for a calibrated European response that goes beyond the IRA (III).

To achieve greater strategic autonomy, the EU must adapt its internal market to the demands of this new era, by combining, on the one hand, a strategy to diversify supply and access external demand and, on the other hand, enhanced innovation and production through the “fair pooling” of capacities that benefits all Member States.

Notes

[1] “The WTO in crisis: Can we do without multilateralism in the digital age?”, Elvire Fabry,

blogpost, Jacques Delors Institute, 9 December 2019.

[2] For the sale of electric vehicles, tax credits are only granted if 40% of the value of critical minerals (extracted or refined) used in the batteries and 50% of the battery components come from the United States or a country that has a free-trade agreement with the United States. These percentages will increase to 100% in 2029. If only one of the conditions is met, the tax credit is limited to $3,750 instead of $7,500. Any tax credit is conditional upon the vehicle being assembled in the United States and ensuring that the battery does not contain minerals or components from unreliable countries, such as China and Russia. However, an exception was granted by the United States in December 2022 for commercial electric vehicles, which do not have to meet these conditions to qualify for tax credits.

[3] “A Green Deal Industrial Plan for the Net-Zero Age”, European Commission, COM(2023) 62 final, 1 February 2023.

SUR LE MÊME THÈME

ON THE SAME THEME

PUBLICATIONS

The Road to a New European Automotive Strategy: Trade and Industrial Policy Options

Make the European Single Market fit for the age of geopolitical competition

Shields Up: How China, Europe, Japan and the United States Shape the World through Economic Security

EU and China between De-Risking and Cooperation: Scenarios by 2035

India and the European Union in 2030

A looming war for minerals?

Taiwan and European strategic autonomy

Achieving net zero while lessening reliance on China

US assertive protectionism

Reducing the EU’s dependence on chinese imports of rare earths and other strategic minerals

China and the role of Europe in a new world order

European companies are facing the decoupling of China and the United States

Les projets importants d’intérêt européen commun (PIIEC)

Building Europe’s strategic autonomy vis-à-vis China

European Strategic Autonomy

and the US–China Rivalry:

Strategic Autonomy

in Post-Covid Trade Policy

Reducing the EU’s strategic dependence

RCEP: the geopolitical impact from a new wave of economic integration

TRUMP’S TRADE WAR: A DELIBERATE CHOICE

Harmful tax competition

The new political economy of Brexit

Industrial subsidies are at the heart of the trade war

Guerre commerciale : « L’Europe peut encore peser »

Meeting the challenges of EU-China relations

The Challenges of Chinese Investment Control in Europe

Screening foreign direct investment in Europe

How can the EU promote its economic interests with China?

Competition, Cooperation, Solidarity: new challenges

Jacques Delors’ “Triptych”: current situation and prospects

For a revival of Europe

MÉDIAS

MEDIAS

« Rien ne réjouit plus Wall Street et Pékin que la fragmentation de l’Europe »

Enrico Letta: “Fragmentés comme on est, on laisse le leadership aux Etats-Unis et à la Chine”

Comment l’Espagne est devenu le nouvel eldorado de la Chine