Other document

The euro and the crises

The euro is not “in crisis” : on the contrary, it is in very good shape as its exchange rate established itself at over 1.4 US dollars in this second part of the month of July – with the disadvantages (for the cost competitiveness of the European products) but also the advantages (especially in terms of energy bills) that this entails. So it would be preferable to refer to the other “crises” that we are experiencing, whilst being more aware that the way in which they are highlighted has very different impacts on the priorities appearing on the agenda of European decision-makers and on the perception of public opinions.

The euro is not “in crisis” : on the contrary, it is in very good shape as its exchange rate established itself at over 1.4 US dollars in this second part of the month of July – with the disadvantages (for the cost competitiveness of the European products) but also the advantages (especially in terms of energy bills) that this entails. So it would be preferable to refer to the other “crises” that we are experiencing, whilst being more aware that the way in which they are highlighted has very different impacts on the priorities appearing on the agenda of European decision-makers and on the perception of public opinions.

If there is a crisis, it is rather an ‘economic and monetary union crisis’, for whichthe assessment up until 2008 was very creditable , but whose governance was ill-suited to cope with the stormy conditions in the marketplace. This governance suffered from its original imbalance, underlined by Jacques Delors and Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa many times, between a lot of emphasis being put on monetary integration, symbolised by the European Central Bank (ECB), and very insufficient economic integration, including in terms of respect for the ‘Stability and Growth Pact’. The recent crisis led to a welcome correction to this imbalance, which was a result of past political compromises from the 1990s. Unimaginable three years ago, the series of European summits bringing together eurozone countries is one illustration of this among others, alongside the active interventions of the ECB on the debt market, the creation of a ‘European Financial Stability Facility’ (EFSF), the substantial reform of the Stability and Growth Pact or the setting up of a ‘Pact for the euro plus’ aiming at a stronger coordination of economic policies and structural reforms. The legislative package on “economic governance” still needs to be adopted and must be implemented seriously and consistently in the coming years. However, what has been “failing” for a few semesters has not been so much Greece as European officials, who have had great difficulty forging aclear vision of the crisis and putting in place acommon and forward-looking approachto deal with it.

This crisis is also and above all a public and private ‘debt crisis’, which goes well beyond the eurozone, as shown by the major financial difficulties experienced by the US but also by the UK despite the devaluation of the pound. This debt crisis constitutes atest for solidarity in the EU, which is not primarily a ‘budgetary test’ as saving a country like Greece requires granting loans of a limited amount given the wealth of the EU, and the same can be said for the loans to Ireland and Portugal (6% of the eurozone’s GDP to the three of them). It is a test of a political nature against a background marked by a hardening of public opinion and messages addressed to the public by national and European officials that are sometimes confused. This test has been passed with the creation of the EFSF, which makes it possible to save countries in financial difficulty and which will now have the option to buy back their debt or to help them in a preventative way. But this success will need to be confirmed as EFSF interventions are subject to highly complex decision-making mechanisms and as its “successor” after 2013, the “European Stability Mechanism”, is not yet fully established. However, it goes without saying that the sometimes excessive criticism of past slips by Greece and weaknesses of countries requesting aid from the EU will hardly have helped things. Nor would the overestimation of the costs of European recovery plans for national budgets, or the difficulty in pointing out that the recovery corresponds to the well understood interest of the countries helping out. It goes without saying that, in this sense, a lot will have to be done to smoothe out the resentments between different countries before even thinking about going into deeper reflection about a possible pooling of national debts via the issuing of ‘European bonds’.

In addition, it is important to underline that the origin of the current difficulties is a financial crisisthat came from the other side of the Atlantic in 2008, as some people sometimes seem to want to have that forgotten by insisting excessively on the ‘crisis of the euro’. In this context, the recent eurozone summit has for the first time adopted a comprehensive and coherent strategy because it is based on a more balanced distribution of effort between countries in difficulty, countries showing solidarity and private creditors. It has been possible to have private creditors to Greece contribute in a ‘voluntary’ way, short of being imposed by a banking tax. Such a mechanism makes it possible to send a nuanced message to the ‘markets’. Above all, it makes it possible to send a useful signal to public opinions as well as to financial actors, whose responsibility is in part committed to the ongoing crisis. In this respect, we would point out that the EU has also envisaged decisive reforms in the area of financial regulation and supervision in order to prevent new crises from occurring. Adopting texts on the solvency of banks, mortgage credit, ‘credit default swaps’, ‘market abuses’ and rating agencies must therefore be considered as a short term priority and be the subject of political mobilisation that is up to the size of what is at stake.

It is in the end an economic and social crisis that is hitting most EU countries. Even if its negative effects have been tempered by the social protection mechanisms of European countries and by the ‘automatic stabilisers’, this crisis also comes with its procession of job losses and material difficulties. Such difficulties could be increased in the countries that have started austerity programmes made necessary by the debt and financial crises. In this context, the EU and its politicians need to send a positive message to all Europeans and to open up the prospects for the future in terms of growth as they have just done for the Greeks. The negotiations underway for the relaunch of the Single Market by 2012, twenty years after the deepening process set in motion by Jacques Delors, provide them with an excellent opportunity to act. The same goes for discussions on European funding for infrastructure and research investment, in the context of thepost 2013 Community budgetor via the issuing of specific European bonds dedicated to these investments.

The current combination of several ‘crises’ should encourage us to use this word cautiously. It is not neutral to talk about the ‘crisis of the euro’ rather than using other more suitable words. Let us hope that heads of state and government can, in this sense, deliver the appropriate messages and responses in the coming months and that officials from the European institutions can do the same. That should start with José Manuel Barroso, whose ‘Speech on the state of the Union’ will come next September at a particularly important time.

Yves Bertoncini

Secretary General of Notre Europe

Notre Europe’s viewpoint has been published inEuractiv.rs(Serbia)

SUR LE MÊME THÈME

ON THE SAME THEME

PUBLICATIONS

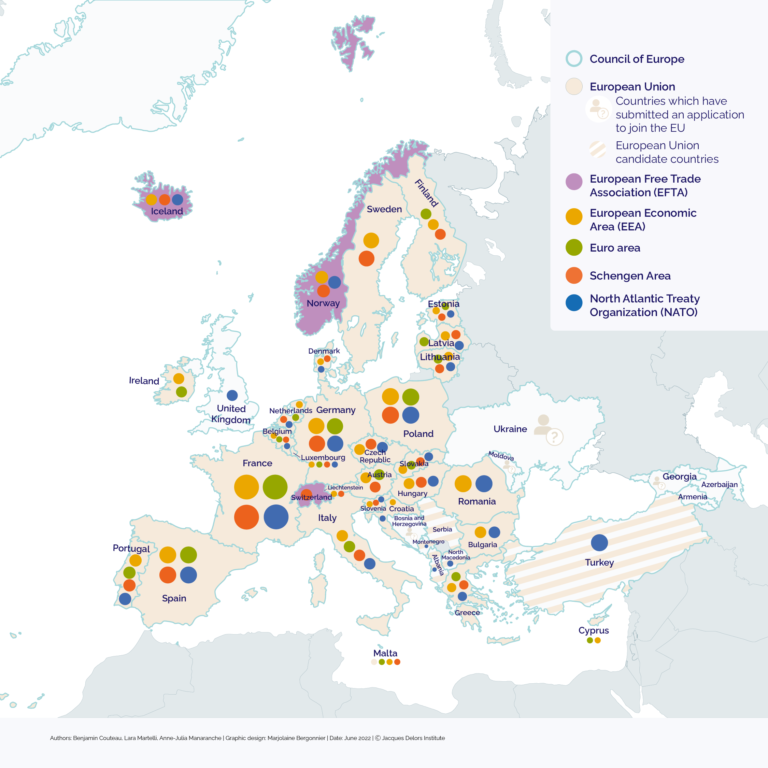

The war in Ukraine:

what are the consequences for European organisations?

After Brexit, euro-denominated derivatives transactions should leave the City

The Euro as seen by citizens who do not yet have it

MÉDIAS

MEDIAS

Marine Le Pen might be about to wreck the eurozone

L’Irlandais Paschal Donohoe reconduit à la présidence de l’Eurogroupe

Il y a vingt ans, l’arrivée des premiers euros